2017- seasons of ..power plant selfies?

How do we define this year? As 2017, a year that many considered exhausting, terrifying, and tumultuous, comes to a close, how do we value it? In the classic song from Rent, “Seasons of Love,” they ask how do you measure a year in the life- “In daylights, in sunsets, In midnights, in cups of coffee?” From the age of 5 to 21, many people have structure; they experience 16 years of summer and winter breaks. Seasons pass and there is always the next gap to look forward to. In adulthood, there are no given moments. We have to create the ones that are important to us. We are left with the question of how we track, measure, and appreciate our years?

I’d like to say I’m measuring my year in terms of where I have been and what I have done. How many new people I have interacted with, cultivated knowledge about and empathy for. How many states I visited for the first time and revisited. How many facilities I wrangled my way into. How many times I sat down to a blank sheet of paper and took the daring step to put my thoughts down, and type the first words of something I would share with the world.

I often find myself writing pieces that justify what I am doing, that show myself what I have done (this one included) and accomplished on paper. Maybe you do the same.

We, as people, and our years, are worth more than what we produce. There are other great things about our years.

For me, this year was about learning and exploration.

One year ago, I didn’t know the difference between transmission and distribution (you don't either? read about how power gets to you). I would pass large facilities on the highway and wonder what was inside. What were the covered mounds of salt or resources alongside large tanks? How did it get there and where was it going? While I may not be able to speak to all the piles, I certainly can spot a coal plant, nuclear plant, or incinerator and have an idea of the inputs.

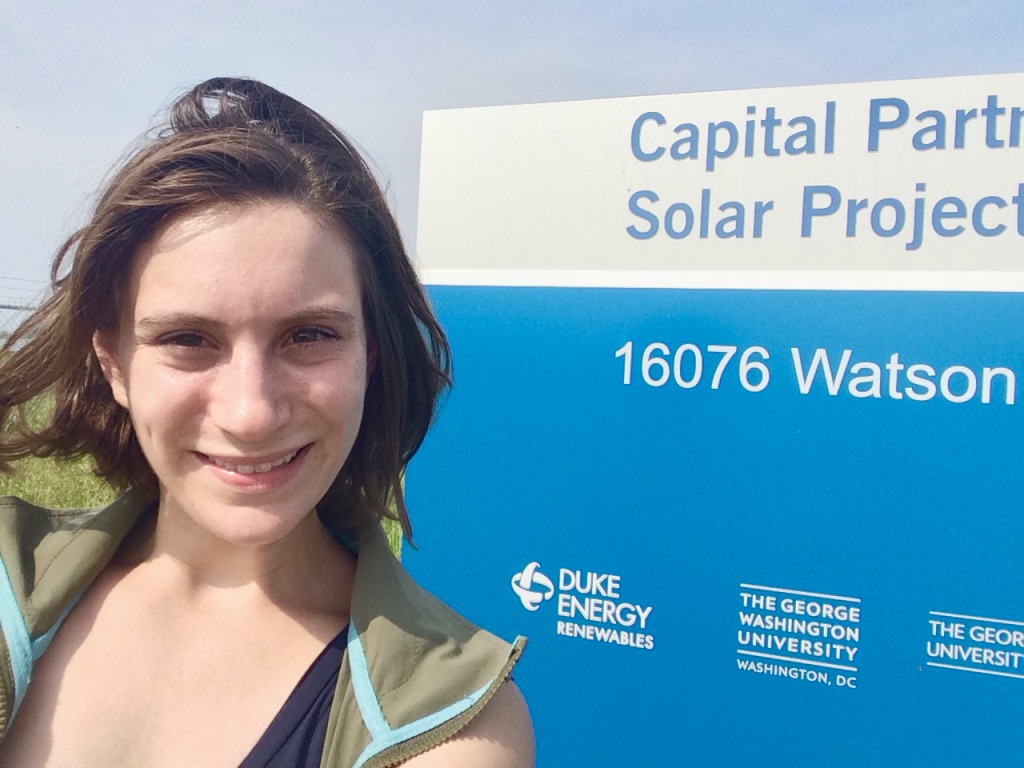

I took the steps to get inside the plants and industry, and indulge my curiosity. And there were people who thought it was worthwhile, who stood beside me, and even financially supported the investigative endeavor. The George Washington University supported the effort with a grant to fund my travels; the World Resources Institute invested resources in helping me cultivate knowledge and exposure. Then there were the people who invested time and money into my exploration, without knowing what would come of it. Duke Energy Renewables opened their doors to me to their largest solar farm in North Carolina and showed me around the Renewable Control Center where they watch their renewable assets. The good people at Covanta’s Newark incinerator endured my harassment when I was working to get an invite to “media day.”

Editors, professors, colleagues, and friends asked around and put me in touch with resources. Strangers tipped me off to when a boat was heading out to the offshore wind farm, and I managed to get on it, and have a moment of career awakening.

People posted on their personal Facebook pages about Electric America and my journey, to share and support the message.

I can say that once I reached a threshold of targeted outreach, the industry was relatively open, receptive even.

I am choosing to count the doors opened; photos taken; smiling selfies at power plants; and whole-hearted endeavors, of which I’ve experienced many. And, of course, situations in which I felt utterly uncertain, and entirely out of my comfort zone.

How are you reflecting on your year? And what do you value from it?

Cheers to this moment and the moments that define your 2017 - whatever they may be. Seasons of smiles, new experiences, cold showers, love notes, frozen computer screens, shared desserts or even selfies at solar farms.