I step on to the site of the Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County (SWA) and cannot believe where I am. Green, purple, and yellow native flowers and palm trees pepper the entryway in front of the Education Center, and twist along the stairwells and walls. The sun beats off the parking overhang, which is covered in photovoltaic panels that generate solar power and keep the cars below cool. The site hosts an integrated solid waste management facility, a trash center, with two large incineration plants that burn trash every day and make electricity. But the site has the twinkle of a brighter time. There is no cloud of smog hovering above or black soot. A single ellipsis-shaped concrete smoke stack jets out into the sky. Unlike typical smoke stacks, this one is not round, the result of a deal made with the surrounding community to minimize the view from nearby properties and ease Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) syndrome. In pictures only a small white stream of pollutants can be seen, and even can be mistaken for moving clouds. Of course, there are emissions associated with the plant, but I’ll get to that later. In the land of beaches and country clubs, the high tech waste to energy plant is beginning to close the loop and effectively utilize the seemingly endless waste stream.

The Facilities

The Solid Waste Authority (SWA) maintains 1,300 acres in total, 300 of which have been set aside as a conservation area. With trails open to the public from dawn to dusk, manmade lakes, and bird habitats, the site serves as an outright natural sanctuary among the populated South Florida area. It was first home to only one incineration plant (Renewable Energy Facility 1, REF 1, built in 1989), which processed half of the county’s garbage at the time. With 50% of the county’s trash going to landfill, the lots were expected to be full by 2020. There were no other sites in the county to build landfills, and after the idea of building one on SWA’s natural site was rejected by the community, SWA sought other options for waste management. It found them in burning more trash and making more power.

The second Renewable Energy Facility (REF 2) (Image 3) opened in 2015 and is known as the newest and most advanced incineration plant in the country. The tour of the facility centered on REF 2, though SWA also has REF 1, two landfills, home chemical recycling centers, a biosolids processing facility (poop processing facility), a recycling plant, and a new LEED Platinum Education Center.

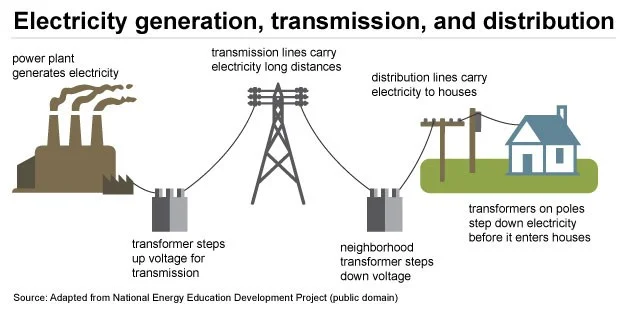

While REF 1 processes garbage to create a “refuse-derived fuel,” REF 2's process is a “mass burn,” which means all garbage received is burned without pre-processing. Massive claws that operate out of a control room grab trash from large piles and move it into a garbage chute, empties into the combustion chamber. The heat created from its burn boils water to make steam, which turns a turbine and generates electricity.

The facility is able to burn everything thrown in the garbage and sort through the ash later because of its emissions control technologies. The stream of byproducts are scrubbed, the acid gases, nitrogen oxides and mercury controlled. The ash then goes through baghouses, or large fabric filters that capture particulates. The facility doesn’t pick out the bad stuff before it’s burned, but rather, prevents it from entering the air. Ferrous and non-ferrous materials are separated from the ash, and the valuable material sold.

Between REF 1 and REF 2, the electricity generated and sold to Florida Power and Light brings in $18M of revenue for SWA annually. REF 2 produces 575kwH of electricity, or about enough to keep your home electrified for half a month, per ton of garbage. It has extended the life of the landfills by approximately 25 years. It is a small power plant, but certainly on the map, in total producing enough energy to power all of the homes in Boca Raton. The $672 million facility has proven to be both a good economic and environmental investment for the county.

The Circular Economy

Given the efficiency of using waste as a fuel- why recycle at all? This question only came up once, during a quick elevator conversation. On the ride down from REF2 with the stragglers of the group, the education specialist explained that burning trash has extended the life of the landfills, but no waste is still better than some waste. Ash will fill the landfills. And it takes a lot less energy and natural resources to recycle something than to extract the resources to create a new product, which can be detrimental to the environment. She continued with the example of aluminum cans- they are, in theory, infinitely recyclable. If all aluminum cans were recycled, we would not need to mine the earth’s crust for aluminum for new cans.

As the tour continued and we moved through the facilities, the connection between natural resource management and energy became clearer. On the SWA site many processes were happening simultaneously to extend the life of products and embedded natural resources -

Waste was burned to eliminate trash and generate electricity; electricity was sent to the grid;

The ferrous material in the ash was separated and sold, further reducing the ash sent to landfill;

Materials that were recycled by homes and businesses were sorted and sold for reprocessing; the glass was used to make glassphalt, a type of shimmering asphalt seen in the parking lot;

The methane release from decomposing trash in the landfill was used to fire the dryers to dry sludge from the waste water treatment plant, which is then turned into fertilizer pellets and used on site for landscaping

The facility clearly is maximizing its resources to minimize the environmental impact. On the van tour, we passed the biosolids processing facility and the landfill. As trash decomposes in the landfill, methane is released into the atmosphere, a greenhouse gas that captures 25x more heat than carbon, therefore accelerating the greenhouse gas effect and climate change. At SWA’s landfill, 60% of the methane is captured and used to power the biosolids processing facility, which receives sludge from the waste water treatment plant, and turns it into fertilizer. While 60% of the landfill methane is sent to the bioprocessing solids facility, the other 40% is flared off, meaning methane is constantly being burned. This is still the cleanest way of methane disposal, as the combustion produces just C02 and water. During the day it is invisible, but you may be able to catch a glimpse at night.

Renewable?

But let’s be clear- incineration is not a form of renewable energy. I agree that it’s a form of waste management, reducing the need to find new sites and ship waste out of the county via polluting trucks. I do, however, take issue with use of the word “renewable.” For the new plant, REF 2, the emissions are controlled and, according to an industry study published on SWA’s website, it produces fewer carbon emissions than coal, oil and natural gas facilities (though it’s not the lowest as far as air quality pollutants- see Table 1). The study is also more forgiving than other estimates and slightly outdated, published in 2005. As a form of electricity generation, it beats fossil fuels when it comes to the effect on climate change.

However, no scientist or renewable energy expert would consider incineration a form of renewable energy. The input for the electricity production, trash, is not inherently a renewable resource. Although it may seem like trash stream is never ending and continually produced, natural resources are being depleted to provide the plastics, metals, containers, products that end up thrown away and burned. Undoubtedly, everything in the waste stream has been extracted from the ground and converted into a user product that is then trashed by the consumer. If a catastrophe hit the earth and shut down production and consumption of goods, the sun would still shine and provide thermal energy. Incineration is not comparable to actual renewable resources, like the sun, tides, and wind, and it is certainly not clean relative to those pollution-free resources.

But in Florida it is. The state of Florida, and 30 other states (plus DC, Puerto Rico, N. Mariana Islands) count incineration as renewable, either by definition in their Renewable Portfolio Standard or in another law. Florida also considers incineration “recycling,” and prescribes one recycling credit per ton of waste incinerated, moving West Palm Beach to the head of the pack for recycling rates in the state. (See if your state considers it renewable here).

Incineration kills two birds with one stone, ridding trash and producing electricity. It reduces the need for new landfills. But as far as energy production, not waste management, it is not the ultimate answer.

Worth a Visit

With its diverse and integrated facilities, the site can draw a crowd. It is cool to see a garbage claw digging through the sum of the county’s garbage, and physically managing it. SWA’s facilities are unique, and housed on a site that exemplifies the intersection of nature and infrastructure.

Because of the breadth of facilities, educational resources, and variety in topic, you are bound to find something that sparks your interest and stays with you after your visit. Between the interactive recycling game and conveyor belt sorting simulation, drone video footage from landfill management, and view of the life sized garbage claw control room something will fascinate, enrage, or enthrall you. If nothing else, you will learn how to recycle better, and that to operate the garbage claw you need at least 7 months of training, unlike the video arcade lookalikes. The site has a modern feel and is one of the most manageable and accessible utility parks around from a visitor’s point of view. Next time you’re thinking about heading to the mall, but want something more meaningful, take a stroll along its Northeast Everglades Natural Area trails or check the schedule for a community tour. SWA gives you unparalleled insight into how you, and your garbage, are fueling the county.

SWA Information:

SWA Trails: http://wpb.org/grassywaters/owahee_trail-php

SWA Tours: http://swa.org/423/Facility-Tours

Note: Lake Worth does not send its garbage or recycling to the Palm Beach County Renewable Energy Facilities; the town has a contract with a waste management provider outside of the Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County.

Additional Resources:

NYTimes: Garbage Incinerators Make Comeback Kindling Both Garbage and Debate

Scientific American: Does Burning Garbage to Produce Electricity Make Sense?

Sources:

SWA

http://www.swa.org/161/Palm-Beach-Renewable-Energy-Facility-1

http://www.swa.org/375/Palm-Beach-Renewable-Energy-Facility-2

Energy Recovery Council

http://energyrecoverycouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ERC-2016-directory.pdf

Corrections- A previous version of this article said REF 1 was built in 1988; it was built in 1989.